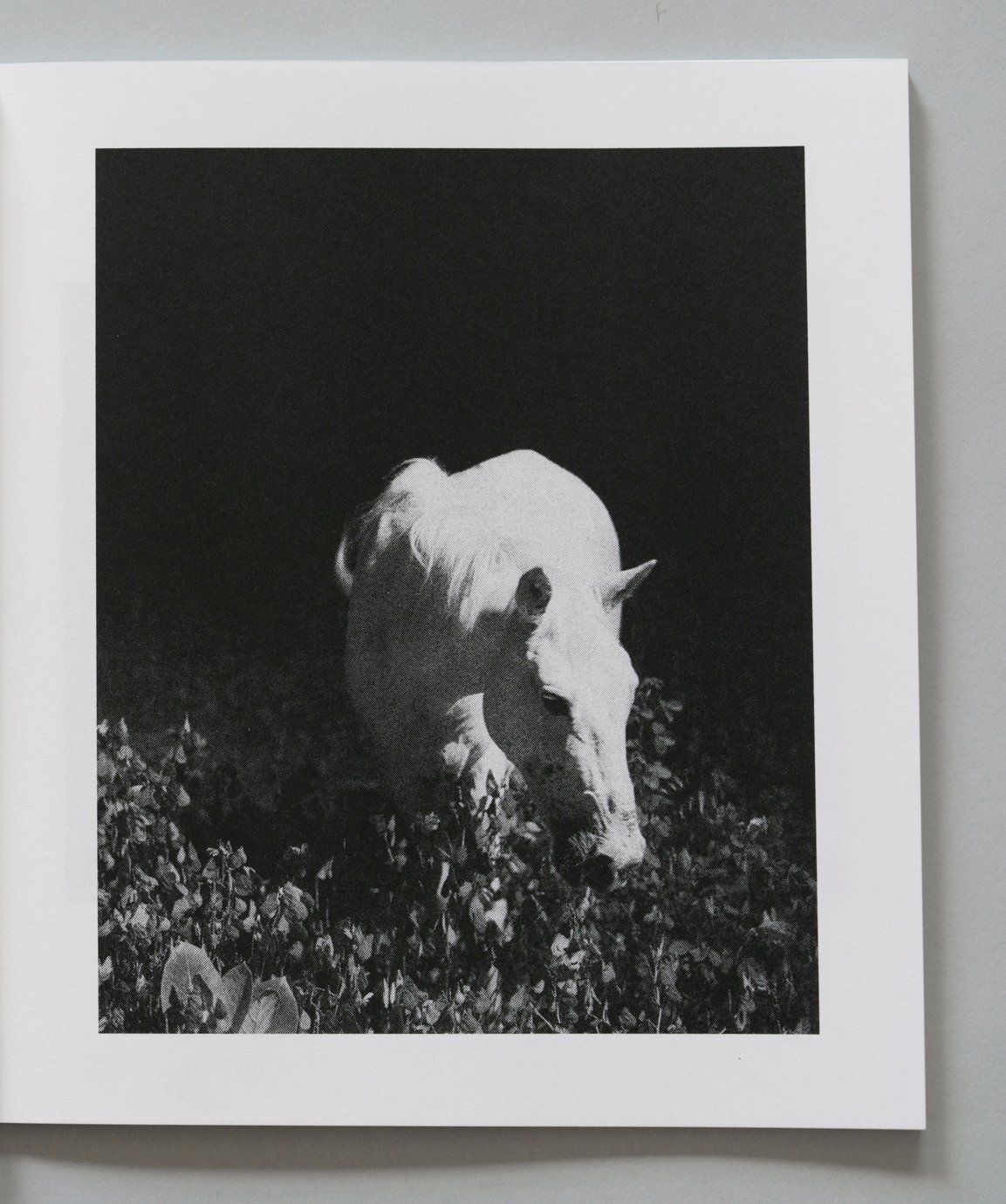

“In this book, American photographer Sophie Barbasch traces her journey along a railroad under construction in Brazil’s northeast. She encounters people and situations that seem suspended in time, rendered almost ghostly by the risograph printing, which transforms her wandering into a succession of dots and shapes to be deciphered. Published by the Penumbra Foundation – an organization that playfully intertwines the artistic and scientific aspects of photography – the book becomes a mysterious, timeless object with neither a clear beginning nor end.”

– Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson

Press / Features:

Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson

Collections:

The New York Public Library

RISD Special Collections

Published by Penumbra Foundation, 2022

Info: Screen-printed Softcover / Risograph Printing / Perfect Binding / 8x9 inches / 37 pages / Edition of 100 with 5 APs / Special Edition of 20 with a signed silver gelatin print / Bilingual (ENG-POR) / Text by Bernardo Carvalho / Design by Karina Eckmeier / Publisher: Penumbra Foundation / 2022 / ISBN: 978-1-7342923-8-1

Project Statement

A train is like a ligament. The route almost has a corporeal form. It engraves itself into the landscape. In the absence of some sort of structure to understand things, I look to railroads and highways, the veins of commerce and connection. These are also, paradoxically, stand-ins for their opposite: for being lost, uprooted, on the loose.

When I was little, my Brazilian stepmother introduced me to a new language and culture. I learned Portuguese and traveled to Brazil regularly, wondering if I was an insider or an outsider. At some point, I decided I needed to go to Brazil on my own. I applied for a grant to photograph the Transnordestina, a railroad under construction in the Northeast that ties the desert to the sea. I lived in Fortaleza for a year, traveling throughout Ceará, Piauí, and Pernambuco.

I followed the route of the train like a map, listening to stories about drought, the emergence of labor unions, and corrupt judges; about quilombos and their sacred spaces; about assentamentos and different political regimes. People told me about the first railroad built by the British and how the colonial shadow has shifted and morphed but never quite disappeared; they told me about anthropologists who came to extract and were followed home by ghosts. These stories exist in different times, registers, and translations. They give way to images that traverse the dark space between languages.

Selected spreads

Mundo-fantasma

Bernardo Carvalho

Embora em princípio não possam ser localizadas no tempo, as fotos brasileiras de Sophie Barbasch têm a atualidade de um sentido que talvez passasse despercebido há alguns anos. São fotos de abandono. Mostram o fracasso de uma promessa. O que se costuma associar ao éthos brasileiro, ao caos e à carnavalização de uma sociedade complexa, brutal e hiperviolenta, injusta e desigual, aqui apenas se deduz pela ausência. Há um anacronismo ao mesmo tempo discreto e misterioso, como se as imagens remetessem a um passado distante cujas ações nunca vemos. O que vemos são as consequências e os efeitos distópicos de iniciativas interrompidas: uma estrada de ferro sem trens, que não leva a lugar algum; um túnel sem saída; o amálgama de restos incongruentes de alvenaria. Se há uma analogia e um diálogo com a atmosfera silenciosa das fotos icônicas de Marcel Gautherot à época heroica da construção de Brasília, é apenas para ressaltar a desolação e a melancolia que a epopeia modernista encobria.

Parte dessa desolação vem do fato de essas imagens retratarem a zona rural nordestina, onde os traços da modernidade não passam de vestígios e ruínas sob a luz eventual de postes de eletricidade pontuando a paisagem árida e estéril. Mas outra parte vem de uma percepção aguda do que é este país, sempre a meio caminho de um projeto abandonado. Mal as coisas são construídas e já estão obsoletas ou destruídas, já são restos e lixo. Vem à cabeça a célebre citação de Lévi-Strauss em "Tristes Trópicos": "Um espírito malicioso definiu a América como sendo uma terra que passou da barbárie à decadência sem conhecer a civilização". Do fogo ao fogo. O que resta é um mundo-fantasma, um deserto onde vagam personagens furtivos cujo silêncio essas fotos registram, como quadros e fragmentos de uma narrativa que também tivesse sido abandonada antes de chegar a formar uma história.

Ghost World

Translation by Thom Mathewson and Kevin Mathewson

Though in theory we cannot locate them in time, the photographs Sophie Barbasch took in Brazil convey a feeling of immediacy that might have passed unnoticed a few years ago. These are pictures of abandonment. They portray a promise that has broken down. The things one commonly associates with the Brazilian ethos - the chaos and the carnivalesque veneer of a complex, brutal, hyper-violent, unjust and unequal society - can only be inferred here by their absence. Her photos impart a sense of anachronism that is at once discreet and mysterious, as though the images invoked a distant past whose actions we can never witness. What we do see are the consequences and dystopian effects of stymied initiatives: a train track no trains have ever run on that leads nowhere; a tunnel with no exit; an amalgam of incongruent bits and pieces of rubble. If an analogy were drawn, if a rapport were to be established with the atmosphere of silence in Marcel Gautherot’s iconic pictures taken during the heroic era of the construction of Brasília, it is only to highlight the desolation and melancholy which that modernist epic poem of a city enshrouded.

Part of this desolation is derived from the fact that these images portray a rural landscape in Brazil’s Northeast, where traces of modernity are confined to remnants and ruins under the haphazard light of lamp posts scattered across an arid and barren terrain. But its other source is an acute awareness of what this country is: eternally stuck at the halfway point in a project that has been abandoned. As soon as something gets built, it is immediately obsolete or destroyed, instantly reduced to leftovers and trash. A familiar quote attributed to Lévi-Strauss’s Tristes Tropiques comes to mind: “A malicious spirit defined America as a land that went from barbarism to decadence without civilization in between.” From fire it comes; to fire it returns. What we end up with is a ghost world: a desert where stealthy figures wander aimlessly, their silence captured by photographs that, like paintings, evoke fragments of a narrative that was itself abandoned before it ever got around to telling a story.