Slideshow performance piece

Photographs taken by my grandfather Mark Barbasch from 1946 - 1958

Printed by me in 2022 (scroll for text and images)

There are moments when the vestiges of collective memory wake me up at night. Charlottesville or other anti-Semitic events will bring back a flood of images that aren’t even mine, forcing me to sit up in bed with a start. Am I trying to hold onto these images? Or are they simply in me—could I never get rid of them, even if I tried?

My grandfather Mark and my grandmother Elsa were Holocaust survivors who met in Paris and moved to Israel/Palestine before coming to America. I never met my grandmother, but I was very close with my grandfather. Growing up and going to Hebrew school, there was a lot of discussion about the Holocaust. He also told me stories from time to time about his experiences as a doctor for the Russian army. He was from Lvov, now Lviv, or at least that is where I believe he was born. I asked him and talked to him about this many times, but recently my mother said: maybe he was born in Vienna. I thought that was surprising. How could we not know?

From a young age, I felt like the Holocaust was something separate from me. As a kid, I didn't know why everyone talked about it so much, since it was clearly in the past. Elsa's experiences in Auschwitz and other camps and her subsequent silence about them seemed to haunt my mother. I thought this was something between them that I would never understand or need to deal with.

The first time I realized this was not the case was when I watched the movie inglorious basterds. My partner at the time thought it would be a fun thing to do. I burst into tears at the end and cried inconsolably. I couldn’t explain it, but the images on the screen were already part of me.

A few years after this, I found my grandfather’s negatives. He had passed away and no one had realized that there was an envelope of about 100 medium format negatives tucked in an album. I was annoyed at my mom, asking why she hadn't told me about this, since I was in school for photography, and I was always looking for something to work on. She told me she had no idea that they existed.

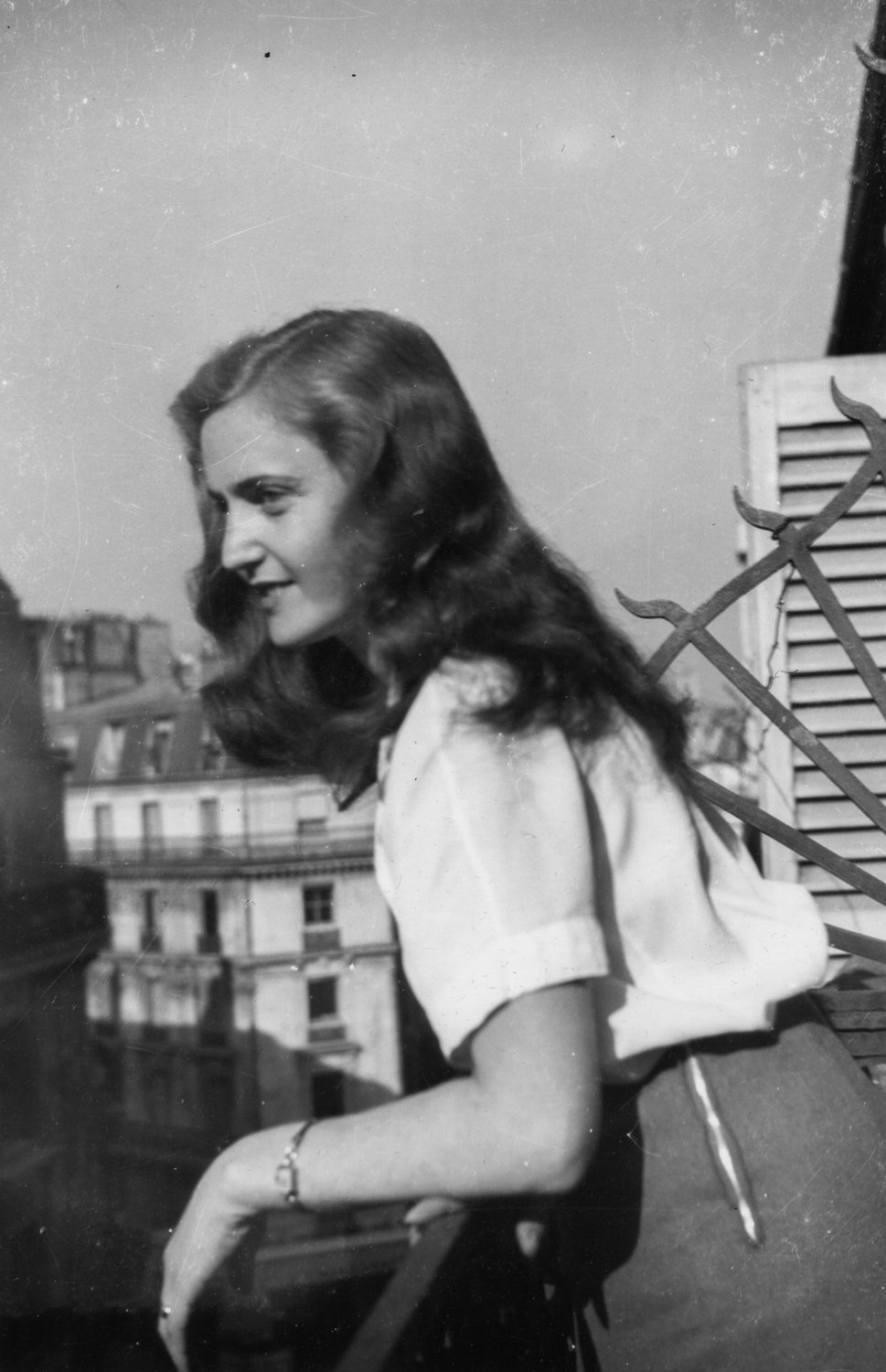

When I held the negatives in my hand, I no longer needed to rely on the images I had invented as a child—of my grandfather dodging bullets in the forest under the Russian moon; of my grandmother being saved from the camps by the Americans, who brought piles of food she was too fragile to eat. Now, I had anchor points, or indices. As I held each negative up to the light, I was “pricked,” as Barthes says—stunned by the sudden weight of this reality.

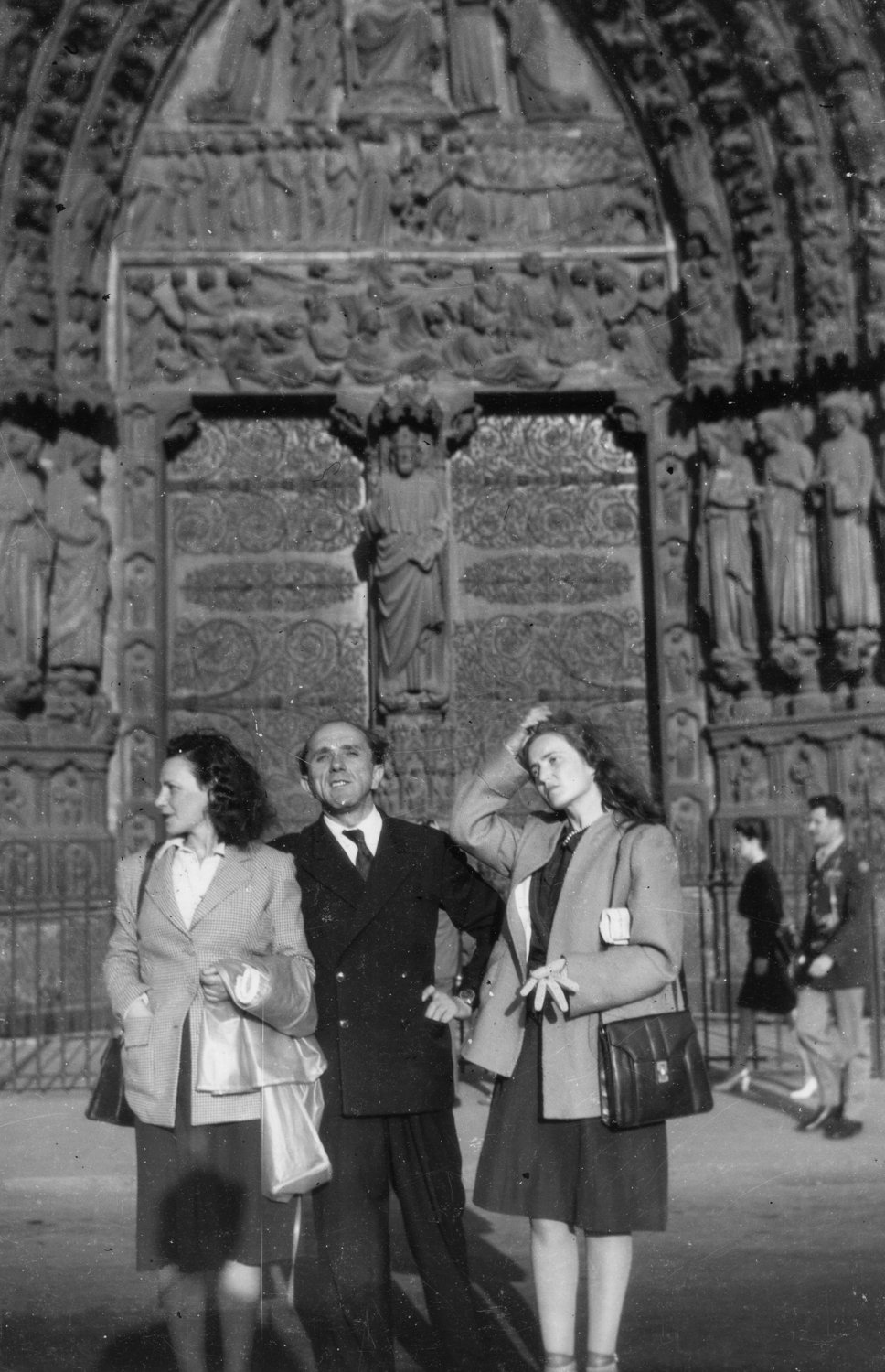

When I made contact sheets, I saw that they visited Notre Dame and one other museum with palm trees outside. The rest of the photos are in train stations, on the street, and on apartment balconies. At first, I was excited to see the images. Then, I was impressed, because they were much more beautiful, and much happier, than I expected.

But there is something sad about them. They confirm the trauma in a way that stories never did. I do the math: how long after the war did this happen? It's a math that they probably did their whole lives. The photographs show concrete moments, and yet, like all photographs, they reveal very little.

I became transfixed by what wasn’t in the pictures. I imagined my grandmother with her two sisters, one of whom died in Auschwitz. Nobody ever referred to her by name. I thought of my grandfather going back home after the war to search for his parents. When he arrived, they were gone and nobody would tell him what happened. He went to ask the building manager, only to find that the man’s house was full of his own family’s things. I wondered, would these memories be supplanted by the new photographs? Was that something I wanted?

The ethics of remembering – of who should remember what and how and when – is what makes memoir, history, and photography so complicated. Sometimes, the majority of the story is left outside of the frame, as it is with these. Here, we see happy tourist photos or images for the family album. There is an aggressive forgetting - a purposeful leaving out. But sometimes it creeps into the frame. Like when I look at the picture of my grandmother on the train just a few years after being deported. For an onlooker with no context, that meaning isn’t there. I wonder if it was there for her as she sat in the station.

Just like that image, which vacillates between two different realities, the archive spans many different roles. At first, my grandparents were refugees after the war and sightseers in Paris, or at least pretending to be - from what I understand, legally they could not stay. (Elsa’s attempt to return home in 1946 was met with a friend’s simple admonition: “don’t.” He had been back, and he didn’t explain further.) They went to Israel/Palestine in 1950 because they could not secure visas to America, and you might define this role according to your politics. They didn't want to experience another war, so when they were finally able to get visas through Elsa’s sister in 1958, they left for the US—immigrants.

At a certain point, my grandfather returned to Europe as a tourist. Still a Jew but also an American, he rode different tour buses and took snapshots in color (an archive of its own) of the Eiffel Tower and the Leaning Tower of Pisa. There is a consumption inherent to the photographic moment that seemed to denote a different power dynamic this time around. In each stage, the pictures are about giving the family an identity. They were also about pretending that a lot of things did not happen.

But as the photographer, wasn’t it my grandfather’s prerogative to excise certain things from the story? Isn’t that both the greatest burden and greatest relief of holding a camera in your hands? Or maybe he didn’t have time or opportunity or desire to make pictures when everything was dire, and maybe there was no way to represent it after the fact.

It is precisely the normalcy of the photographs that allows me to see my grandparents as just themselves – as just normal young people. It allows me to see them both inside and also separate from history: not just a morality tale, not defined by tragedy. This is what gives the images a startling sense of life. Maybe it’s not about forgetting the war so much as remembering what was there in spite of it.

In line with remembering and forgetting, my mother got me books on intergenerational trauma that I managed to avoid. She gave me books by W.G. Sebald, which I read but then felt I had hallucinated, as though every word was forgotten the second it was apprehended. But the process of printing, storing away, thinking about, and returning to these negatives forced me to confront the overlapping emotional space with my mother, her mother, and myself.

The mystery for me is still the space between thought and emotion, between conscious and unconscious awareness. I can focus on printing an image and appreciate that my grandmother looked happy one day in the 1940s. The next day, I have trouble going back into the darkroom, and I don't know why. This fluidity between experience, image and memory, all moving together in inscrutable ways, comes up again and again while working on this project.

At one point, I asked my mother to give me the huge shopping bag full of the other archive—the paperwork. I thought I'd just go through it, cull important things, and make an informative edit. But every piece of paper was intense. There was the history of the war scrawled on a napkin in my grandfather's handwriting detailing where he was, where Elsa was, at major points of the conflict. There was the picture of a young soldier with an ambiguous note to my grandmother wishing her luck on her wedding day. Who was that? There were the printouts of my grandmother's records from the camps that my uncle got from the D.C. Holocaust museum. It pained me to read the Nazi's detailed notes on her height, weight, hair, eye color. I felt angry that I was finding out about her eye color from the Nazis. And then I realized that I knew her eye color from photos and must have somehow forgotten that too.

Sometimes I wonder if I should just leave these images alone - what if my grandpa doesn't want me showing them? But then I think of the pointed effort to make these pictures. Sometimes a scene was photographed two or three times. The film made it through many borders. Like the napkin, these photographs feel like his missives to the future. When I find myself under that same spell of silence that afflicted my grandparents and later my mother, I tell myself it’s something that he wanted to share.

I spend a lot of time staring at the images and trying to figure out what to do with them. I think I am expecting them to instill a sense of order or understanding. But under the surface, the disorder percolates. They are stand-ins for all the other images we inherit from our predecessors, if only semi-consciously. It makes me think of osmosis, the movement of molecules through permeable membranes. The divisions—temporal, emotional, physical—that I thought existed simply don't exist. I think it's a gift that these pictures could make me understand this.

Both the field of photography and the field of Holocaust studies have a strange relationship to remembering and forgetting. Growing up, forgetting was the absolute worst thing you could do. But now it occurs to me that I can't forget, and that remembering and forgetting look different than I thought.